Designing, developing, and refining FAZA was a process that involved making many mistakes, slowly noticing them, and then making thousands of small design decisions – eventually accumulating into a cohesive experience that I can finally say is fun. This is the one constant in designing any product, service, or experience: making mistakes. We as designers make a lot of them. It’s only through testing prototypes that we discover mistakes and have the opportunity to fix them.

The First FAZA

FAZA originally began as a quasi-tower defense game that mashed together a few different game mechanics I enjoyed. The players controlled heroes that would be responsible for saving and defending their camp from the onslaught of FAZA drones, dropped off from motherships.

FAZA also incorporated a way to add more tiles to the board as the game unfolded. The prototype was somewhat playable, but I discovered problems with pace due to board management. Game play was slowed because players had to move too many FAZA pieces while also navigating the board with their avatars.

Cutting Rules through Playtesting

Since FAZA is a cooperative game, the players are responsible for managing the foe they’re playing against. The challenge was to reduce the amount of pieces that players had to move around the board, while ensuring the game was challenging. From another perspective, I was also looking to free up more time for players to have dialogue with each other so they could focus on making interesting decisions as a group. The more time they spent managing the board the less time they could engage the core of the game.

At this point, my time was spent playtesting to identify rules I could cut, which was followed by more playtesting to make sure the game was still playable. Cut, playtest, tweak, playtest – it was grueling and required a lot of dedication to get past this hump. The persistence slowly began to manifest, it helped me discover the core of the game. This took me roughly a year to get through.

By cutting away the game mechanics that were too time consuming and less enjoyable the foundation for the game was now set. It was time to invest in the graphical work and illustrations.

Illustrations

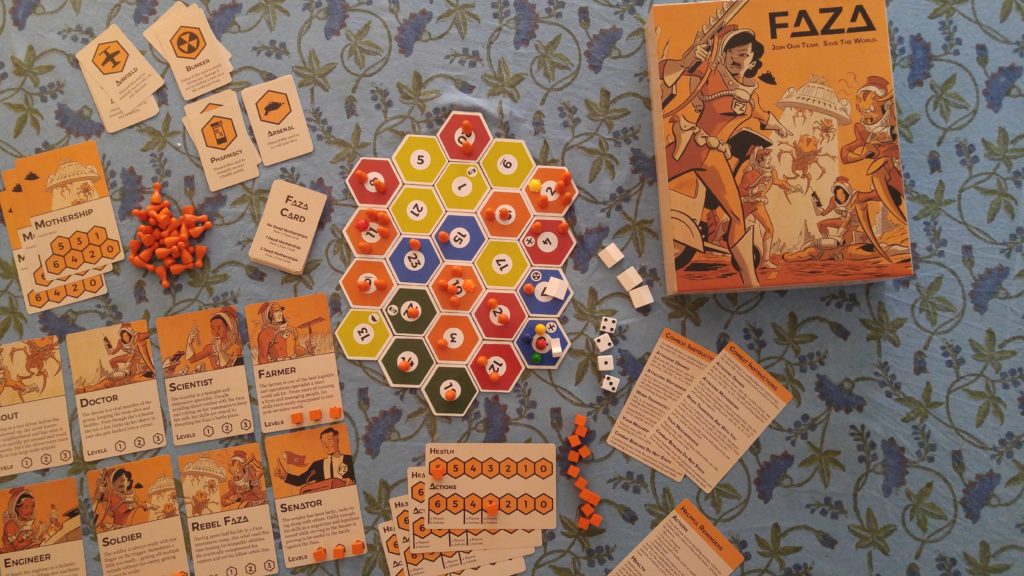

Another major step in the design process involved working with an illustrator and solidifying the aesthetic, lore, and backstory to the game. This went a long way to make the game look and feel complete, drawing people in to sit down and play. But it wasn’t enough; the game mechanics were still rough around the edges, the choices presented to players were bland, and the user interface still needed a lot of work.

Player Choices

The next big step in the design process was accounting for the different choices players were making to battle and defeat the FAZA. I wanted to ensure each decision presented players with trade-offs. If a player chooses A, then they have to give up B. To promote dialogue, I also worked towards a design that forced players to make tough choices while strategizing as a group. These are the kinds of choices tacticians have to make, and this added tension to every player’s experience.

The cards in front of them functioned as their user interface, presenting them with all their options and choices, scaffolding their decision making process. Thinking through and mapping out the available choices for players was the next big hurdle in the game design process. It informed the design of the Player Cards, which are now core to playing FAZA.

Refining the User Interface

Just as important as the other aspects of the design process is visually communicating to players the options they have in front of them. All interfaces have a learning process and carefully observing people struggle to learn the game, noting what they find confusing, and adding visual cues and text reminders went a long way to scaffold their learning process.

Finding FAZA’s Audience

FAZA is not for everyone. The level of strategic thinking, tactical coordination, and cooperative dialogue demanded of players can be a turn off for some people. There have been many times where I’m two minutes into explaining how to play the game and I can see a player’s eyes glaze over. Before people sit down to playtest FAZA, I repeat multiple times we can stop playing the game and they can leave at any time. I think giving players the option to get up and leave ensures I don’t waste their time and they don’t waste mine. Since it’s a 90 minute time investment, I want FAZA to be a fun and enjoyable experience. Discovering FAZA’s audience then involved having conversations with everyone that played the game, learning about what other kinds of games they’re into, other hobbies and activities they engage in, and what drew them to FAZA.

Facilitating Playtesting Sessions

Another vital step in the game design process is facilitating user testing sessions to extract actionable insights. For me, it involved observing people while remaining detached as they struggle to learn to play the game. I would then ask a few prepared questions post-playtest.

While I’ve been designing games only for the past two years, I’ve been doing user experience research and design for about 7 years. One particular strategy I employed from my professional work to get the most out of playtesting is using the think-aloud protocol. As the name implies, think-aloud protocol asks players to verbalize what they’re looking at, what they’re thinking through, and the decisions they want to make. Occasionally, I would interject to probe with a few ‘why’ questions to better understand their thought process and experience. While this particular strategy can quickly reveal many issues, it will greatly increase the play time and you probably won’t get through an entire game. It also requires you to not play your game and instead sit quietly on the sidelines, take notes, and do your best to deflect any questions back to players in order to see if they can find the answer they’re looking for.

I would argue playtesting is the most important aspect of the design process and also the most time intensive. To speed up that process, I started reaching out to local board game stores and accidentally came in contact with a local board game design group called the Game Makers Guild of Philadelphia. They’re game designers who get together twice a month to playtest each others board games and give each other feedback.

If it were not for the continued playtesting and feedback from friends, family, and the Game Makers Guild of Philadelphia, I don’t think I would have been able to bring FAZA to where it is today.

Questions or Comments?

If you have any questions or comments or want me to write another post going into further detail about any of the points I outlined above, leave a comment below.

How did you find the artist for your game. Also how did you approach paying for their services if you have not yet published your game. Was this self funded or was some sort of arrangement made upon delayed payment or profit shares?

My brother-in-law, who also works as a graphic designer, found the artist. I communicated the overall style I had in mind and he provided a list of a few illustrators he thought matched the aesthetic. I then went through the illustrator’s site, looked at their work, proceeded to contact them, and then negotiated a contract. Without my brother-in-law’s help, I would have been pretty lost since I wasn’t steeped in this world to begin with. He also guided me with contract negotiation with the illustrator, since I had never hired an artist before.

The art was then paid for fully out of my pocket with money I’ve saved up from my day job. I feel uncomfortable offering profit shares or delayed payment for a few reasons:

1) Since this is the first board game I’ve brought to this level of polish and development, I’m still figuring out how to market FAZA and the eventual payments that would trickle in from a profit share would have taken years before reaching the levels that would make sense for the illustrator. Essentially, the illustrator would have taken financial risk to do a profit share or delayed payment. I also tend to keep my expectations low as to the potential units that might eventually be sold because I know it takes a long time to get any business going. As a point of reference, I’ve also been working on small business for about 5 years, and it has taken a significant amount of work and persistence to make it sustainable.

2) If I do a profit share, I would be interested in a longer term relationship or partnership. So, our goals and timelines would have to align, which is a tough state to reach if the working relationship is new or non-existent. This also means I would use profit sharing as a way to motivate someone to work with me for a few years, if not longer, like a decade.

3) Since I knew that marketing of the game would be on the timescale of years, I had assumed that if I ever wanted to work with the artist again, he would be less likely to do more art if the profit share yielded unfruitful results and low sales.

One more thing I just realized from your questions, which I forgot to mention in the post, is that the illustrations were completed two rounds. The goal of the first round of art was to make FAZA presentable at game conventions so people would stop by and play. So I focused the art on the fewest amount of pieces that would make the game presentable and immersive, in this case it included the characters and the cover. This was a way for me to validate two things: if the general aesthetic I had in mind would meld with the game mechanics, and if the mechanics combined with the art resonated with people. This approach also reduced the financial risk for me.

After I had tested the game with close to hundred people and FAZA won The Game Crafter’s Big Box Challenge, I felt comfortable investing more into the game. So I went back to the same artist to do a second round of illustrations. This second go through added art to the remainder of the game, which includes terrain tiles and unique motherships.

I hope this is helpful. I’ll turn this comment into a post, other game designers might actually find this to be a useful read. Let me know if you have any more questions or comments, I’ll do my best to address them all.

Are you a game designer by any chance? Have you gone through this process? I’m actually curious to see how other game designers approach this, since this is the first time I’ve had to worry about adding art to a game I’ve designed.

Thanks Ben. I am designing a card game at the moment which could require a lot of artwork. I am currently working thought the rule book at the moment finalising initial game mechanics, game play/ flow and card types. Once that’s all sorted I will be making the first sweep through to make all the different cards so have already started thinking about what artwork may be required and how I’m going to find the artists I need to make it all. The game will still work with a smaller artwork base, but I know that the people who will play this will crave and almost expect to have unique artwork per card. Not sure the best way to approach looking for artist or what sort of contract arrangements are fairly standard for game designers who need artwork without the financial backing to support it.